Metrics

Halo Canada studies are modelled on studies first carried out by Partners for Sacred Places and the University of Pennsylvania's School of Planning and Policy in the City of Philadelphia.

Cnaan, R.A. , Tuomi Forrest , Joseph Carlsmith & Kelsey Karsh (2013): “If you do not count it, it does not count: a pilot study of valuing urban congregations”, Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, DOI:10.1080/14766086.2012.758046 Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14766086.2012.758046

NOTE: The values in our studies are constantly evolving as new research becomes available. While we endeavor to keep this page as current as possible, applicable metrics are available by contracting us directly at [email protected]

A. Open Space:

1. Green Space: Many congregations have trees, lawns, gardens and other green spaces on their property, each of which has positive impact on the aesthetic and environmental status of the neighbourhood.[1], [2]

At the time of our Toronto pilot, the City of Toronto was considering implementing a storm-water management fee of $0.77 per square meter to be applied to impermeable property area (roof, asphalt, and concrete areas, etc.). To monetize some of the value of green space in our study, we incorporated this value by using satellite images[3] to measure the area of impermeable property for participating congregations. The city of Toronto did not proceed with this fee and, as a result, we eliminated this calculation rom our study following the Toronto pilot.

The Philadelphia study also sought to include a detailed valuation of tree contributions to pollution reduction and water runoff control making use of a tool developed by the US Forrest Service.[4] When considering the time intensive nature of collecting these measurements in more than 50 congregations; that only 4 of 12 congregations in the Philadelphia study reported economic contributions of over $1000 in this category; and that only two reported contributions of over $5,000, it was decided to also eliminate this item from the matrix.

In addition to the concrete methods identified above, other studies[5] document how green spaces and recreational areas can have a positive effect on the value of residential properties located close and in turn generate higher tax revenues for local governments. This impact depends on the distance between the residential property and the green space as well as the characteristics of the surrounding neighbourhood. A recent study conducted in Dallas – Fort Worth showed that houses within 500 feet of a green space with an average size over 2 acres showed a percentage added value of approximately 8.5%, while those located within 100 feet had a percentage added value of almost 25%. [6] Another study of three neighbourhoods in Boulder, Colorado suggests that property values decrease by $4.70 USD for each foot away from a greenbelt area.[7] While the extent of these valuations is significant and recognized anecdotally, attributing index values to these components are beyond the scope of this study.

Some congregations add value to their green space by making them available for garden plots. Peleg Kramer[8] cites a New York study which measured the value of produce from 43 gardens (17,000 pounds of food) at approximately $52,000 USD ($66,638 CDN) for an average of roughly $1550 CDN. There was no indication of the size of these community gardens. In order to err on the conservative side, we estimated that an average garden plot would yield $775 dollars worth of food annually.

2. Recreation - Children’s Play Structure: Currently the City of Toronto, Parks, Forestry and Recreation enhances/replaces existing Toronto playgrounds under its play enhancement program. Playgrounds being enhanced/replaced under this program currently have a Capital Budget of $150k each. This is a global budget that includes: professional and technical service fees, testing and permit costs (as required), management fees, construction/installation costs and applicable taxes. Typically the playground equipment cost (including installation) accounts for $50-70k of that global budget. This range can vary from playground to playground based on a wide number of factors. Where play structures are present, we anticipate that, on average, they would not be of the size and scope of City facilitated structures. To maintain a conservative estimate we estimate an avg. cost of $30,000 for commercially installed structures with a life span of 25 years. This would equate to an average yearly valuation of $1200.

3. Recreation – Sports Field: The Philadelphia study based their valuation on a U.S. Corps of Engineers Study,[9] which estimated the annual benefit to direct users of sports fields/facilities at a minimum of $5000 USD (apr. $6500 CDN) annually. We were unable to identify a similar Canadian study and as a result used the following calculations. Parks and Recreation for the City of Toronto books outdoor diamonds and fields in 2-hour blocks. These facilities are available on a seasonal or spot rental basis. Average charge is approximately $25 per hour. We estimated that a soccer field / baseball diamond / cricket pitch on congregational property might be used an average of 1 hour per weekday and 2 hours per weekend day from April to October (252 hours) at $25/hr for a total annual valuation of $6300.

4. Parking: Congregational parking lots are used most often by members coming for worship or other congregational events. In some cases, congregations may offer this space for a fee to monthly or daily users. In many cases, however, parking is offered free of charge as long as it is not considered `regular ‘use. To estimate the value of publicly available parking, we searched the average value in up to three nearby lots and applied the difference between the municipal value and what the congregation churches. In locations where there are no public lots available and/or whether ample street parking is available we did not apply any socio-economic value.

5. Property Tax: Typically, faith communities are not taxed on their properties. However, one of the participants in our initial phase study is located in the downtown core and has a long-term lease arrangement with a developer for an office tower that was constructed on the property. This arrangement provides significant benefits to the city through taxation and as such provides a “halo” impact. To calculate the value of this impact we cite an article that states: that in 2012 the average commercial tax assessments were $31.85 per $1000 of assessment.[10] We also discovered through a public rental website that the property includes 240,000 square feet. Assessments are usually determined on the basis of rental income, but construction costs can also serve as a proxy. Altus Group[11] estimates construction costs for buildings 30 storeys and taller to be between $265 and $365 / sq. ft. Following the lowest cost scenario, an equation based on the variables stated above produces an annual tax assessment of $2,025,660.

B. Direct Spending

6. Operational Budget: In 1999, Chaves and Miller[12] provided the first systematic review of congregational budgets, and found that congregations tend to save very little of the income they receive. Typically congregations spend as much as they receive in revenue. As such, their total expenditures can largely be seen as economic contributions to their local community. Congregational budgets are spent mostly on salaries, music programs, social services, maintenance and upkeep, all of which tend to be local expenditures and thus provide stimulus to the local economy.[13] Most congregational staff tend to live locally and therefore spend the bulk of their salary locally. A certain portion of the salaried budget is, of course spent outside the community, as are certain non-salaried portions of the budget such as organizational contributions, international development, and disaster relief but these amounts tend to be relatively small proportionally speaking. To take this fraction into account we estimate (in-line with the Philadelphia study) that the congregation`s base-level contribution to its local economy is 80% of its annual operating budget.

7. Other Budgets: Some congregations maintain more than one budget. For example, congregations might hold separate budgets for music, youth programming, or men’s’ and women’s’ groups. To ensure that all budgets were included, we asked specifically for these additional budgets (excluding capital budgets which are identified below as a separate category). We applied the same thinking as above and counted 80% of each separate budget as a contribution to the local economy.

8. Capital Projects: Because of their very specific nature and often limited time frame, capital budgets are almost always separate from the operating budget. Constructing a new building or undertaking major renovations often require different kinds of strategic planning and fund-raising. In these kinds of situations, it is often necessary to engage architects and contractors from outside the community. In order to account for this reliance on “out-of-neighbourhood” services, we estimated that only 50% of capital campaign or building budgets are spent locally.

9. Special Projects (not included above): Some special projects involve applications to foundations, government organizations, religious organizational offices and business. While some of these grants may be intended to address internal congregational needs, it would appear the vast majority of these types of grants are intended to address the wider community. In keeping with items 6 and 7 (above,) we estimate that 80% of each of these types of funding be seen as a contribution to the local economy.

.

C. Education

10. Nursery School / Day Care: To apply value in our earliest studies for this benefit, we measured the money that child-care programs save parents by allowing them to work full time. According to the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, Toronto has the highest rates in Canada for infant child care ($1676) as well as the highest toddler fees at ($1324). We took the average of these two figures which equates to $1500 per month.[14]. This puts the average yearly cost of childcare at $18,000. A parent who is therefore able to work full- time (40 hrs/wk, earning a minimum wage (Ontario - $11.40/hr) for 50 weeks a year earns an annual income of $22,800. By subtracting from this the average yearly childcare cost of $18,000, we find a net benefit of $4,800 per child in care.

More recently, we have employed a value arising out of a study by the Obama White House administration[15] This study suggests that early childhood education can: 1) narrow the achievement gap, 2) boost children’s earnings later in life, 3) create gains that outweigh the costs, 4) help parent’s balance work and family responsibilities, 5) lower involvement in the criminal justice system, 6) reduce the need for remedial education and its associated costs. This study estimates that these dynamics contribute to an annual estimated benefit of $20,236 CDN / child.

11. Alternative Schools: Where congregations are involved in providing space and/or opportunities for alternative education we applied value by applying the Ministry of Education’s reported cost of education for the province in which the congregation is situated. For example, In Ontario, the Fraser Institute reports that in 2016/2017 (the most recent year for which Statistics Canada is available) the cost per student to provincial tax- payers was $13,321. It follows, that if these students are not enrolled in public education, this presents am equivalent savings to society.

12. Musical Instruction

D. Magnet Effect

13-22. Conferences, weddings, funerals, religious festivals and rites of passage and other events often attract significant numbers of visitors to the congregational site. These visitors often spend significant amounts of money while in the neighbourhood. In total, we identified 10 areas that contribute to “Magnet Effect”. In the Philadelphia study, Cnaan et al (2013) attempted to differentiate between the numbers of people who might travel overnight for an event vs. those who were simply making daytrips into the community. In our study, we elected not to include overnight stays, believing these estimates would be too difficult to verify. Instead, we opted to make use of Ontario Ministry Tourism estimates that place the average same day visit spending to be around $82. Applying the same rationale used by Cnaan et al (2013) to apply this value to only 1 in 4 visitors, we settled on an average value of $20 per visitor. We then applied either reported estimates of those travelling greater than 10 km to each event or applied the corresponding percentage of worshippers who travel more than 10km to worship as a proxy.

23. Members Expenses While in the Neighbourhood: As illustrated in sections 12-21, visitors to the neighbourhood are estimated to spend an average of $20 per visit. If the individual, or family, simply drive in and out of the neighbourhood, their financial contribution will be minimal. But if they purchase gas, buy groceries, visit a local resident or go shopping at a nearby mall their spending will increase significantly. In the Philadelphia study, estimates of this daily value were confirmed with over 30 interviews of members who commute from outside the neighbourhood to attend services. As a result, we applied the same $20 amount per person for those travelling greater than 10 km to worship. (This does not take into account times when they may have driven in to attend mid-week meetings or programs).

E. Individual Impact

24. Suicide Prevention: Assessing the value of life is a difficult topic socially, let alone in financial terms.[26] It is commonly assumed that the two key costs of suicide and attempted suicide are lost income and cost of health care. This assumption excludes the notion of attributing a value to the grief of family and friends. The Canadian Mental Health Association reports that the cost of suicidal death ranges from $433,000 to $4,131,000 per individual depending on potential years of lost life, income level and economic impacts on survivors. The estimated cost of attempted suicide ranges from $33,000 to $308,000 per individual depending on the level of hospital costs, rehabilitation, family disruption in terms of lost income, and support required following the attempt.[27] While it is difficult to assess whether or not preventing a suicide over the course of a year prevents suicide in subsequent years, we followed the assumption offered by Cnaan et al (2013) that it can conservatively be estimated that preventing someone from committing suicide for one year saves a 20th of the cost of suicide. Using their model, we added $33,000 (the lowest estimate of the cost of attempted suicide) and 5% of $433,000 (the lowest estimated cost of a successful suicide) to arrive at a value of $54,650. It should be noted that this figure does not include an economic value for the cost of grief, emotional trauma, and other personal suffering.

25. Helping People Gain Employment: Many congregations are active in helping congregational members and/or community residents gain full-time employment. In order to assess this value, we use the corresponding provincial minimum wage for each study congregation at a conservative estimate of 35 hours/week for 50 weeks per year. In Ontario, in 2020, the current minimum wage is $14 per hour. This translates to a corresponding annual salary of $24,500.

26. Crime Prevention: Some congregations also report that they have been active in preventing congregational or community members from going to prison. Cnaan et al (2013) report that this should be seen as a distinct from the general influence congregations may have as examples of “moral influence” (i.e. promoting good behaviour, social cohesion and respect for the law). In this section of the study, however, we are focussing on direct impact, examples of crime prevention where clergy or other members of the congregation were directly responsible for preventing this kind of outcome. Statistics Canada reports that it costs an average of $357 each day to maintain an adult in federal prison and $172 to imprison someone in Provincial Correctional Facilities.[28] To arrive at an appropriate index we took the average of the two ($264.50) and multiplied the figure by 365 for a total of $96,542.50. To this figure, Cnaan et al. added a figure of $5,000 in minimum taxes that the government no longer receives from the imprisoned person, bringing the total to $101,542.50. We applied this value each time a congregation reported directly preventing someone from going to prison.

27. Helping End Alcohol and Substance Abuse: Many faith communities are also active in helping people end alcohol and substance abuse. While there may be indirect assistance offered by being connected to a faith community, as well as membership in affiliated support groups such as AA, our study involved only direct counselling from clergy or other congregational staff. We asked each clergy team to identify the number of individuals they believed they had had a direct role in ending a person’s alcohol or substance abuse. Then in order to value this contribution we reviewed the literature on economic cost of these factors on society. In 2002, it was estimated, that the economic costs to society of substance abuse have reached $39.8 billion in Canada[29]. Of these economic costs, approximately $24.3 billion was due to labour productivity losses, including short-term and long-term disability and premature mortality. Health Canada estimates that social costs for alcohol and substance abuse are comprised primarily of health and enforcement costs. In terms of alcohol related costs they estimate $165 (health) and $153 (enforcement) for a total of $318 per occurrence. With respect to substance abuse they estimate $20 (health) and $328 (enforcement) for a total of $348. This leaves us with an average value of $338 per occurrence.[30] It should be noted that these figures are considerably lower than the estimate of $15,750 put forward by Cnaan et al (2013).

28. Enhancing Health and Reducing the Cost of Illness: The Canadian Institute for Health Information reports that the average health costs per person are $6105 annually.[31] It has also been reported that early diagnosis (particularly in the area of dementia and diabetes which represent two of Canada`s greatest public health challenges) can reduce health costs by as much as 30%.[32] Taking these figures into account we applied an index value of $1831 in situations where congregations have through some means been able to assist with early diagnosis or access to health care. While this is often difficult to assess it is most clearly evident in situations where a Parish Health Nurse or some other Medical or Mental Health Professional is part of the congregational staff.

29. Exercise Programs: Katzmarzyk and Jansen (2001) estimate that inactivity accounts for 2.6% of the total annual Canadian Health Cost. In 2016, that value was estimated to be $219 Billion. 2.6% of that amount is 5,694,000,000 or approximately $5.7 billion. Canada’s population in 2016 was 36,268,378 which equates to $156.70 per person. As a result, we applied $157 to every person who the congregation involved in a regular program of physical activity.

30. Teaching Children Pro-Social Values: Cnaan et al (2013) point out that one of the reasons families with young children join faith a community is to ensure that their young children receive a moral education, are taught social values and learn something of the value of civic engagement. Regardless of religious tradition, communities of faith offer educational programs and children`s activities that encourage social responsibility, moral commitment, and respect for authority. These programs are difficult to value. For the most part, the costs for these programs are embedded within congregations` general budgets. Cnaan et al contacted some groups who did charge for youth programming and devised a formula which suggests the value of teaching a young person pro-social values is $375 per year. We were unable to identify similar programs in the Canadian context. One way of valuing this role would simply be to apply the current CDN exchange rate to the figure proposed by Cnaan et al. This would produce a value of $484.25. Another way would be to ascribe a modest value of $10 per week which would equate to an annual value of $520 (very close to the proposed exchange rate (to err on the conservative side we elected to go with $484.25 per identified child 12 years and under).

31. Promoting Youth Civic Engagement: Several studies support the economic value of teaching youth civic behaviour.[33] They contend that religious participation, as well as participation in other forms of extra-curricular activities is a significant predictor of political and civic involvement and that these youth are less likely to engage in risky behaviours that bear cost to society. Sinha et al[34] are careful to note that congregational influence represents only one of many factors including parental care, school input as well as peer influence. In terms of ascribing economic value to this dynamic, the clearest offering we were able to identify is put forward by Cohen and Piquero.[35]They suggest that the potential benefits of encouraging civic behaviour is similar to that of dissuading a young person from adverse societal behaviours such as truancy, drug use, criminal activity and abusive behaviour towards peers. They conclude that the monetary value of “saving” a high-risk youth is between 2.6 and 5.3 million dollars (US). With a midpoint of approximately 3.95 million over a 50-year lifetime, the annual savings is approximately $79,000 (USD) or $102,013 (CDN). However, not all youth are “high-risk” and so we reduced the estimate by 75% (1 in 4). Furthermore, faith communities are not alone in helping youth avoid illegal or risky behaviours. Parents, teachers and other organizations all have a role to play in supporting them. And so, we reduced the figure by another 75%, arriving at a final estimate of $6379 (CDN) annually for each identified youth between the ages of 13 and 18.

32. Helping Immigrant and Refugee Families Settle in Canada: To apply value in this area our earliest studies relied on a report by the Ontario Council of Agencies Serving Immigrants reports that it costs an average family of three approximately $55,000 - $65,000 a year for living expenses. Many faith communities are involved in sponsoring refugee families from abroad.[36] This includes not only covering these costs for a period of up to one year but assisting with: helping to find suitable long-term housing, helping to learn English or French, assisting with job search, helping them to learn about Canadian culture and values, and helping them to access services and programs within the community. Assuming that there are costs beyond the minimum average “hard” cost of $55,000, early in our assessments we took the difference between the two estimated values to apply a valuation of $60,000 per family (in this case regardless of family size). Suspecting, however, that this value was low, we asked five of the study congregations who had been involved in refugee sponsorship to provide detailed estimates of time spent, in-kind donations and factored these values alongside study estimates of the socio-economic benefit for society of these activities. As a result, we estimate the value of sponsoring a thee-member family to be $124,942[37]

33. Preventing Divorce: Clergy sometimes are able to support married partners in ways that help to prevent divorce. In order to measure this impact, we asked clergy to indicate the number of married partners that they could reasonably state would likely have separated or divorced without their direct influence. In Canada, an uncontested divorce will cost approximately $1,000. However, a recent poll of 570 Canadian lawyers indicates that cost for a contested divorce ranges from $6,582 to as much as $86,644, with the average running about $15,570.[38] It is recognized, however, that the prevention of divorce by a ministry professional such as Pastor, Rabbi or Imam or any designated members of a congregation may not be permanent. Couples may simply be postponing divorce until a later date. For this reason we followed the example of Cnaan et al, counting the figure of $15,570 as being applicable if the couple stayed together for another 20 years. Dividing by 20, we estimate the value of preventing a divorce for one year is worth approximately $780.

34. Helping End Abusive Relationships: In 2013, Justice Canada released a report indicating that domestic violence and spousal abuse costs the country at least $7.4 billion a year.[39] Drawing on almost 50,000 instances of spousal abuse reported to police, and a 2009 Statistics Canada phone survey which estimated that 336,000 Canadians were victims to some form of violence from their spouse. Dividing the estimated cost by the number of victims yields an annual per victim cost of $22,023. As with divorce, it is possible that prevention may not be permanent. Applying the same 20-year logic model, dividing by 20, we estimate the value of helping end an abusive relationship for one year to be worth approximately $1100.

F. Community Development

35. Job Training: Congregations, particularly in urban settings, are often involved with individuals in need of job training. In 2006, Cnaan et al conducted a census of congregations in the City of Philadelphia, in which they asked about the cost of congregational-based job training programs. The reported average cost was approximately $10,000 per program. Our study chose to address this question differently; on the basis of per individual cost. To approximate an appropriate value we explored other publicly offered programs. The YMCA in Toronto offers courses that provide one-with-one counselling, assessment tools such as Myers Briggs and Emotional Quotient Inventory, detailed interpretation of the assessment results and follow-up sessions for ongoing support and guidance. Depending on the amount of time these programs range and length of ongoing support these programs range from $470 to $610 to $870.[40] Assuming that most individuals would choose the middle category we settled on a figure of $610 per individual for job-training programs.

36. Housing Initiatives: Housing programs are amongst the most demanding types of projects that congregations can undertake. They require substantial amounts of funding, long-term commitment, and the support of a wide variety of partners and stakeholders. In cases where congregations have undertaken these commitments we propose calculating direct costs for construction pro-rated over an assumed 50 year life-span. In addition to this, Toronto Community Housing Identifies a market value rate of $1060 per family-sized unit.[41] In order to attribute an approximate value to society for Housing Initiative Involvement we adopted the following equation: (cost / 50 years) + (number of units created x $1060/month or $12720) minus rent paid and government subsidies applied.

37. Lending Programs: Faith based organizations, including local congregations, have a rich tradition of involvement in developing the social economy of Canada.[42] One such example is where faith-based organizations have been involved in lending programs to assist families in extreme need or to facilitate small business and micro-industry. In cases where congregations have undertaken this kind of support, we propose basing value on the actual amount of funds loaned.

38. Small Business and Non-Profit Incubation: Some faith communities are involved in helping incubate or initiate small business or micro-enterprises. Cnaan et al[43] found that the average investment of congregations who were involved in incubating small businesses was $30,000. In our study, we chose to use employment generated. Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada identifies a micro-business as 1 to 4 employees.[44] We assumed that any start-up business would likely fall within this category. We estimated an average number of 2 employees unless specifically stated. Again using the minimum wage calculation for two individuals we arrived at a total annual value of $39375 for the creation of a small business. This estimate is conservative and does not take into account the investment of the owners or taxes generated.

G. Social Capital and Care

Most faith communities, regardless of tradition provide space for social programming that benefits people in the wider community. For the most part, their operating budget covers at least part of the cost of these programs. For example, the cost of clergy and staff time, utilities and building maintenance are generally included in operating budgets. Some additional costs; however, are not covered. They include the following three items: space value, volunteer time, and in-kind support.

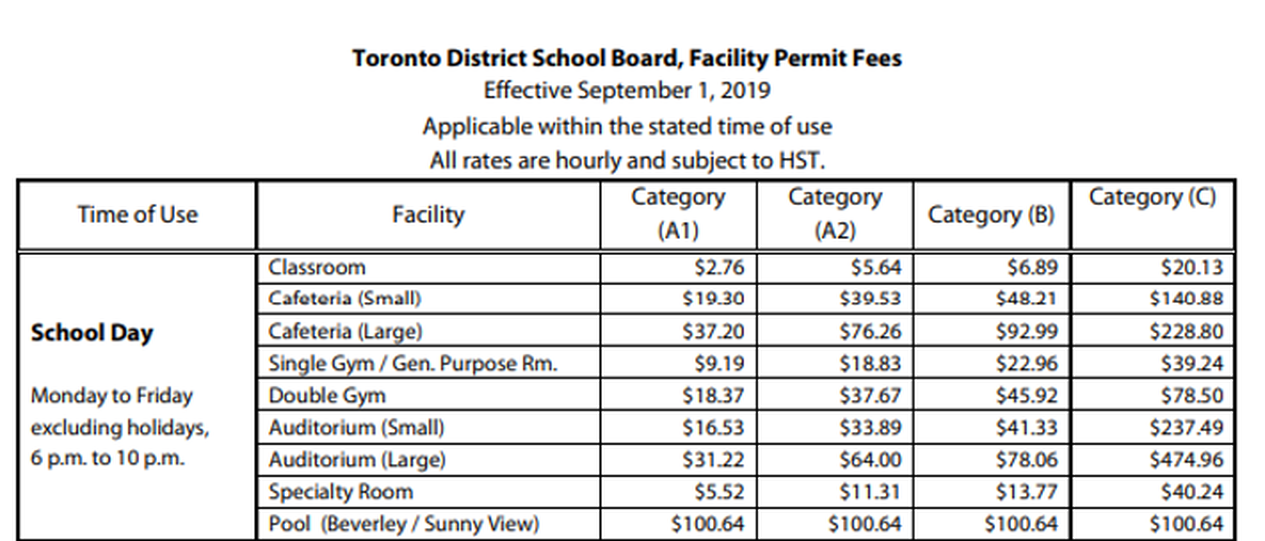

39. Value of Social Program Space: We asked congregations to complete program templates for each program they provide or support that is open to and provides some touch-point with the wider community. Following Cnaan et al, we followed the replacement method which assumes that if a public or private organization was to provide this program, they would have to rent an equivalent space. Following this method, if a faith community provides its social program space for free, then the value of the space represents an economic contribution to the local community.[45] If the congregation rents out the space at below-market value, then we applied the difference between market value and what was received in fees. To determine market value costs for use of space we relied on information published by the local school board in each locale. For example, for the 2019/2020 school year the Toronto District School Board charges the following rates:[46]

NOTE: The figures represented above do not account for any security, technical, or client support services that are often provided and/or required by the Toronto District School Board in addition to the rates indicated above.

In situations where groups have continuous and/or exclusive use of space we have approximated based on publicly advertised lease rates for equivalent space in that locale.

Where the participating group is charged market value for the space, we applied a value of $0.

40. Value of Volunteer Time: Volunteers serve as a major resource for all congregations.[47] According to the 2011 United Nations State of the World’s Volunteerism Report, “…volunteerism benefits both society at large and the individual volunteer by strengthened trust, solidarity and reciprocity among citizens, and by purposefully creating opportunities for participation.”[48] In 2010, Statistics Canada conducted the most detailed study of volunteerism in Canada to date. Notably, for this research, StatsCan observed that 21% of people who attended religious services once a week were considered top volunteers, compared with 10% of people who attended less frequently (including adults who did not attend at all). Moreover, the StatsCan study revealed that almost two-thirds of Canadians aged 15 and over who attended religious services at least once a week (65%) did volunteer work, compared with less than one-half (44%) of people who were not frequent attendees (this includes people who did not attend at all). The study also revealed that, volunteers who are weekly religious attendees dedicated about 40% more hours than other volunteers: on average, they gave 202 hours in 2010, compared with 141 hours for other volunteers.[49] We considered volunteer work in two areas: a) operating the congregation, b) providing social programs. Our earliest studies cited a value of $24 for every volunteer hour contributed.[50] More recently however, Statistics Canada has upgraded this value to $27 per hour.[51]

41. Social Program In-Kind Support: Many congregational programs directed towards the community are supported through various types of in-kind support. A typical example would be a food or clothing drive. Sometimes these involve one-time events or supporting ongoing programs. Other types of in-kind support include transportation, school supplies and household items. For each social program the congregation reported on we asked them to estimate the amount of in-kind support they provided. We added these estimated costs across the various programs to estimate an annual contribution.

It should also be noted that in some cases, a benefit for some may be a detriment to others. Cnaan et al[52] cite the example of where a member of the clergy may help to prevent a divorce which may benefit that family but might undermine the business of local divorce lawyers. Our study does not attempt to measure.

References Cited

[1] Curran, Deborah (2011), “Economic Benefits of Natural Green Space Protection (The POLIS Project on Ecological Governance and Smart Growth BC)”. Available from: http://www.smartgrowth.bc.ca/Portals/0/Downloads/Economic%20Benefits%20of%20Natural%20Green%20Space%20Protection.pdf

[2] Lindsay, Lois (2004), “Green Space Acquisition and Stewardship in Canada’s Urban Municipalities”, Evergreen. Available from: http://www.evergreen.ca/downloads/pdfs/Green-Space-Canada-Survey.pdf

[3] Google (n.d.). “Google Maps”. Available from: https://www.google.ca/maps

[4] US Forrest Service (2010), iTree. Available from: https://www.itreetools.org/

[5] Kerr, Jacqueline (2011), “The Economic Benefits of Green Spaces, Recreational Facilities and Urban Developments that Promote Walking”, in Quebec en Forme Research Summary 4:2. Available from: http://www.quebecenforme.org/media/5875/04_research_summary.pdf

[6] Miller, A., (2001), “Valuing Open Space”, Land Economics and Neighbourhood Parks. Cambridge, MA. Massachusetts Institute of Technology Centre for Real Estate.

[7] Walker, Christopher, (2004) “The Public Value of Urban Parks”. (The Urban Institute: Washington DC) Available from: http://www.urban.org/research/publication/public-value-urban-parks

[8] Kramer, Peleg, (2012), “Quantifying Urban Agriculture Impacts, One Tomato at a Time”, Triple Pundit May10, 2012. Available from: http://www.triplepundit.com/2012/05/quantifying-urban-agriculture-impacts-one-tomato-time/

[9] US Army Corps of Engineers (2010). “Recreation: Value to the Nation”. Available from: http://www.corpsresults.us/recreation/recreation.cfm

[10] Perkins, T., (2012). “Developers Decry High Commercial Property Taxes.” In Globe and Mail Oct 15, 2012. Available from: http://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/developers-decry-high-commercial-property-taxes/article4611934/

[11] Altus Group (2014). ”Construction Cost Guide – 2014”. Available from: http://www.altusgroup.com/media/1160/costguide_2014_web.pdf

[12] Chaves, M. and S.L. Miller (1999). “Financing American Religion.” Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira

[13] Cnaan, R., Bodie, S.C., McGrew, C.C. and J Kang, (2006), “The Other Philadelphia Story: How Local Congregations Support Quality of Life in Urban America.” Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press

[14] Macdonald, David and Martha Friendly (2014). “The Parent Trap: Child Care Fees in Canada’s Biggest Cities.” Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives: Ottawa. Available from: https://www.policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/National%20Office/2014/11/Parent_Trap.pdf

[15] Obama White House Administration (2015), “The Economics of Early Childhood Investments”. Available from: https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/docs/early_childhood_report_update_final_non-embargo.pdf

[16] Statistics Canada (2017). “Wages by Occupation”. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/180626/dq180626a-eng.htm

[17] Canada Revenue (2018), “Canadian Income Tax Rates for Individuals – Current and Previous Years”. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/tax/individuals/frequently-asked-questions-individuals/canadian-income-tax-rates-individuals-current-previous-years.htmls

[18] Province of Ontario (2018), “Ontario 2019 and 2018 Personal Marginal Income Tax Rates”. Available from: https://www.taxtips.ca/taxrates/on.htm

[19] Catterall, J.S., Dumais, S.A., and G. Hampden-Thompson (2012), “The arts and achievement in at-risk youth: Findings from four longitudinal studies.” National Endowment for the Arts – Research Report #55. Available from: https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/Arts-At-Risk-Youth.pdf

[20] Lasby, D., and C. Barr (2018), “30 years of giving in Canada – The giving behaviour of Canadians: Who gives, how and why?” Imagine Canada and Rideau Hall Foundation. Available from: http://www.imaginecanada.ca/sites/default/files/30years_report_en.pdf?pdf=30-Years-Main-Report

[21] Conference Board of Canada (2018), “The Value of Volunteering in Canada.” Available from: https://volunteer.ca/vdemo/Campaigns_DOCS/Value%20of%20Volunteering%20in%20Canada%20Conf%20Board%20Final%20Report%20EN.pdf

[22] Albright, L., (2013), “Creative Spaces and Community Based Arts Programming for Children and Youth”. Arts Network for Children and Youth. Available from: https://www.artsnetwork.ca/sites/default/files/ANCY_GovofCanadaProposal_2013FederalBudget_0.pdf

[23] Arts Health Network of Canada (2010), “Impact of Arts on Health”. Available from: https://artshealthnetwork.ca/ahnc/images/impact_of_arts_on_health.pdf

[24] New Economics Foundation (2014), “Well-being in four policy areas: Report by the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Well-Being Economics.” p. 39. Available from: https://b.3cdn.net/nefoundation/ccdf9782b6d8700f7c_lcm6i2ed7.pdf

[25] Hankivsky, O., (2008), “Cost Estimates of Dropping out of High School in Canada.” Published by the Canadian Council on Learning. Available from: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.510.4857&rep=rep1&type=pdf

[26] Robinson, J.C., (1986). “Philosophical Origins of the Economic Valuation of Life.” Millbank Quarterly 64(1):133-155

[27] Canadian Mental Health Association (2016). Mental Illness in Canada: Statistics on the Prevalence of Mental Disorders and Related Suicides in Canada. Found at: http://alberta.cmha.ca/mental_health/statistics/

[28] Statistics Canada (2015). “Adult Correctional Statistics in Canada 2013/2014”. Available from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/85-002-x/2015001/article/14163-eng.htm

[29] Rehm, J., Baliunas, D., Brochu, S., Fischer, B., Gnam, W., Patra, J., Popova, A., Sarnocinska-Hart, B., and B. Taylor (2006), “The Costs of Substance Abuse in Canada. Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse: Ottawa. Available from: ”http://www.ccsa.ca/Resource%20Library/ccsa-011332-2006.pdf

[30] Thomas, G and C. Davis, (2009), “Comparing Risks of Harm and Costs to Society.” Visions 5(4):11 Available from: http://www.heretohelp.bc.ca/visions/cannabis-vol5/cannabis-tobacco-and-alcohol-use-in-canada

[31]Canadian Institute for Health Information (2015). “Health Spending Data”. Available from: https://www.cihi.ca/en/spending-and-health-workforce/spending

[32]Barchester Foundation, (2010). “Early Dementia Diagnosis Could Reduce Costs by 30%” Available from: https://www.barchester.com/news/early-dementia-diagnosis-could-reduce-costs-30

[33] Smith, E., (1999). “The Effects of Investments in the Social Capital of Youth on Political and Civic Behaviour in Young Adulthood: A Longitudinal Analysis.” Political Psychology, 20(3), 553-580

[34] Sinha, J.W., Cnaan, R., and R.J. Gelles, (2006). “Adolescent Risk Behaviours and Religion: Findings from a National Study.” Journal of Adolescence, 30(2):231-249

[35] Cohen, Mark and Alex Piquero (2007), New Evidence on the Monetary Value of Saving High Risk Youth (Vanderbilt University School of Law and Economics). Pp. 1-58. Found at: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1077214

[36] Janzen, R., (2016) Unpublished Manuscript. “Canadian Christian Churches as Partners in Immigrant Settlement and Immigration.” Centre for Community Based Research: Waterloo. pp. 1-31

[37] Wood Daly, Mike (2018), “Refugee Support And the Socio-Economic Impact of Canadian Faith Communities.” Unpublished paper.

[38]Vaz-Oxlade, Gil (2013). “Keep Divorce Out of Court.” MoneySense. Available from: http://www.moneysense.ca/columns/super-saver/keep-divorce-out-of-court/

[39] Zhang, Ting and Josh Hoddenbagh, Susan McDonald, Katie Scrim, (2009), An Estimation of the Economic Impact of Spousal Abuse in Canada, 2009. Government of Canada: Department of Justice. Found at: http://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/cj-jp/fv-vf/rr12_7/index.html

[40] YMCA Career and Employment Training. Found at: https://ymcagta.org/employment-and-immigrant-services/career-planning-and-development-services

[41] Toronto Community Housing (2016), TCHC Annual Budget 2016. Found at: http://www.torontohousing.ca/webfm_send/13077

[42] McKeon, B., Madsen, C., and J. Rodrigo (2009), “Faith-Based Organizations Engaged in the Social Economy in Western Canada.” The BC- Alberta Social Economy Research Alliance pp. 3-34

[43] Cnaan et al (2006)

[44] Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (2013), “Key Small Business Statistics – August 2013.” Available from: https://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/061.nsf/eng/02808.html

[45] Cnaan et al (2006).

[46] Toronto District School Board (2020), “Toronto District School Board Fees.” Available from: https://www.tdsb.on.ca/Portals/0/community/Permits/G02_Permit_Fees%202019-20.pdf

[47] Cnaan et al (2006)

[48] United Nations Volunteers. (2011). “State of the World's Volunteerism Report: Universal Values for Global Well-being.” Found at:. www.unvolunteers.org/swvr2011 .

[49] Statscan (2011). “Volunteering in Canada.” Available from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/11-008-x/2012001/article/11638-eng.htm#a13

[50] Volunteer Canada. Found at: https://volunteer.ca/value

[51] Conference Board of Canada (2018). “The Value of Volunteering in Canada”. p. 10. Available online at: https://volunteer.ca/vdemo/Campaigns_DOCS/Value%20of%20Volunteering%20in%20Canada%20Conf%20Board%20Final%20Report%20EN.pdf

[52] Cnaan et al (2013)

Cnaan, R.A. , Tuomi Forrest , Joseph Carlsmith & Kelsey Karsh (2013): “If you do not count it, it does not count: a pilot study of valuing urban congregations”, Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, DOI:10.1080/14766086.2012.758046 Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14766086.2012.758046

NOTE: The values in our studies are constantly evolving as new research becomes available. While we endeavor to keep this page as current as possible, applicable metrics are available by contracting us directly at [email protected]

A. Open Space:

1. Green Space: Many congregations have trees, lawns, gardens and other green spaces on their property, each of which has positive impact on the aesthetic and environmental status of the neighbourhood.[1], [2]

At the time of our Toronto pilot, the City of Toronto was considering implementing a storm-water management fee of $0.77 per square meter to be applied to impermeable property area (roof, asphalt, and concrete areas, etc.). To monetize some of the value of green space in our study, we incorporated this value by using satellite images[3] to measure the area of impermeable property for participating congregations. The city of Toronto did not proceed with this fee and, as a result, we eliminated this calculation rom our study following the Toronto pilot.

The Philadelphia study also sought to include a detailed valuation of tree contributions to pollution reduction and water runoff control making use of a tool developed by the US Forrest Service.[4] When considering the time intensive nature of collecting these measurements in more than 50 congregations; that only 4 of 12 congregations in the Philadelphia study reported economic contributions of over $1000 in this category; and that only two reported contributions of over $5,000, it was decided to also eliminate this item from the matrix.

In addition to the concrete methods identified above, other studies[5] document how green spaces and recreational areas can have a positive effect on the value of residential properties located close and in turn generate higher tax revenues for local governments. This impact depends on the distance between the residential property and the green space as well as the characteristics of the surrounding neighbourhood. A recent study conducted in Dallas – Fort Worth showed that houses within 500 feet of a green space with an average size over 2 acres showed a percentage added value of approximately 8.5%, while those located within 100 feet had a percentage added value of almost 25%. [6] Another study of three neighbourhoods in Boulder, Colorado suggests that property values decrease by $4.70 USD for each foot away from a greenbelt area.[7] While the extent of these valuations is significant and recognized anecdotally, attributing index values to these components are beyond the scope of this study.

Some congregations add value to their green space by making them available for garden plots. Peleg Kramer[8] cites a New York study which measured the value of produce from 43 gardens (17,000 pounds of food) at approximately $52,000 USD ($66,638 CDN) for an average of roughly $1550 CDN. There was no indication of the size of these community gardens. In order to err on the conservative side, we estimated that an average garden plot would yield $775 dollars worth of food annually.

2. Recreation - Children’s Play Structure: Currently the City of Toronto, Parks, Forestry and Recreation enhances/replaces existing Toronto playgrounds under its play enhancement program. Playgrounds being enhanced/replaced under this program currently have a Capital Budget of $150k each. This is a global budget that includes: professional and technical service fees, testing and permit costs (as required), management fees, construction/installation costs and applicable taxes. Typically the playground equipment cost (including installation) accounts for $50-70k of that global budget. This range can vary from playground to playground based on a wide number of factors. Where play structures are present, we anticipate that, on average, they would not be of the size and scope of City facilitated structures. To maintain a conservative estimate we estimate an avg. cost of $30,000 for commercially installed structures with a life span of 25 years. This would equate to an average yearly valuation of $1200.

3. Recreation – Sports Field: The Philadelphia study based their valuation on a U.S. Corps of Engineers Study,[9] which estimated the annual benefit to direct users of sports fields/facilities at a minimum of $5000 USD (apr. $6500 CDN) annually. We were unable to identify a similar Canadian study and as a result used the following calculations. Parks and Recreation for the City of Toronto books outdoor diamonds and fields in 2-hour blocks. These facilities are available on a seasonal or spot rental basis. Average charge is approximately $25 per hour. We estimated that a soccer field / baseball diamond / cricket pitch on congregational property might be used an average of 1 hour per weekday and 2 hours per weekend day from April to October (252 hours) at $25/hr for a total annual valuation of $6300.

4. Parking: Congregational parking lots are used most often by members coming for worship or other congregational events. In some cases, congregations may offer this space for a fee to monthly or daily users. In many cases, however, parking is offered free of charge as long as it is not considered `regular ‘use. To estimate the value of publicly available parking, we searched the average value in up to three nearby lots and applied the difference between the municipal value and what the congregation churches. In locations where there are no public lots available and/or whether ample street parking is available we did not apply any socio-economic value.

5. Property Tax: Typically, faith communities are not taxed on their properties. However, one of the participants in our initial phase study is located in the downtown core and has a long-term lease arrangement with a developer for an office tower that was constructed on the property. This arrangement provides significant benefits to the city through taxation and as such provides a “halo” impact. To calculate the value of this impact we cite an article that states: that in 2012 the average commercial tax assessments were $31.85 per $1000 of assessment.[10] We also discovered through a public rental website that the property includes 240,000 square feet. Assessments are usually determined on the basis of rental income, but construction costs can also serve as a proxy. Altus Group[11] estimates construction costs for buildings 30 storeys and taller to be between $265 and $365 / sq. ft. Following the lowest cost scenario, an equation based on the variables stated above produces an annual tax assessment of $2,025,660.

B. Direct Spending

6. Operational Budget: In 1999, Chaves and Miller[12] provided the first systematic review of congregational budgets, and found that congregations tend to save very little of the income they receive. Typically congregations spend as much as they receive in revenue. As such, their total expenditures can largely be seen as economic contributions to their local community. Congregational budgets are spent mostly on salaries, music programs, social services, maintenance and upkeep, all of which tend to be local expenditures and thus provide stimulus to the local economy.[13] Most congregational staff tend to live locally and therefore spend the bulk of their salary locally. A certain portion of the salaried budget is, of course spent outside the community, as are certain non-salaried portions of the budget such as organizational contributions, international development, and disaster relief but these amounts tend to be relatively small proportionally speaking. To take this fraction into account we estimate (in-line with the Philadelphia study) that the congregation`s base-level contribution to its local economy is 80% of its annual operating budget.

7. Other Budgets: Some congregations maintain more than one budget. For example, congregations might hold separate budgets for music, youth programming, or men’s’ and women’s’ groups. To ensure that all budgets were included, we asked specifically for these additional budgets (excluding capital budgets which are identified below as a separate category). We applied the same thinking as above and counted 80% of each separate budget as a contribution to the local economy.

8. Capital Projects: Because of their very specific nature and often limited time frame, capital budgets are almost always separate from the operating budget. Constructing a new building or undertaking major renovations often require different kinds of strategic planning and fund-raising. In these kinds of situations, it is often necessary to engage architects and contractors from outside the community. In order to account for this reliance on “out-of-neighbourhood” services, we estimated that only 50% of capital campaign or building budgets are spent locally.

9. Special Projects (not included above): Some special projects involve applications to foundations, government organizations, religious organizational offices and business. While some of these grants may be intended to address internal congregational needs, it would appear the vast majority of these types of grants are intended to address the wider community. In keeping with items 6 and 7 (above,) we estimate that 80% of each of these types of funding be seen as a contribution to the local economy.

.

C. Education

10. Nursery School / Day Care: To apply value in our earliest studies for this benefit, we measured the money that child-care programs save parents by allowing them to work full time. According to the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, Toronto has the highest rates in Canada for infant child care ($1676) as well as the highest toddler fees at ($1324). We took the average of these two figures which equates to $1500 per month.[14]. This puts the average yearly cost of childcare at $18,000. A parent who is therefore able to work full- time (40 hrs/wk, earning a minimum wage (Ontario - $11.40/hr) for 50 weeks a year earns an annual income of $22,800. By subtracting from this the average yearly childcare cost of $18,000, we find a net benefit of $4,800 per child in care.

More recently, we have employed a value arising out of a study by the Obama White House administration[15] This study suggests that early childhood education can: 1) narrow the achievement gap, 2) boost children’s earnings later in life, 3) create gains that outweigh the costs, 4) help parent’s balance work and family responsibilities, 5) lower involvement in the criminal justice system, 6) reduce the need for remedial education and its associated costs. This study estimates that these dynamics contribute to an annual estimated benefit of $20,236 CDN / child.

11. Alternative Schools: Where congregations are involved in providing space and/or opportunities for alternative education we applied value by applying the Ministry of Education’s reported cost of education for the province in which the congregation is situated. For example, In Ontario, the Fraser Institute reports that in 2016/2017 (the most recent year for which Statistics Canada is available) the cost per student to provincial tax- payers was $13,321. It follows, that if these students are not enrolled in public education, this presents am equivalent savings to society.

12. Musical Instruction

- Earning Potential – The Toronto Arts Foundation reports that 8% of those who are engaged in the Arts are more likely to aspire to more professional (better paying) jobs. If the median salary in Canada[16] is $26.09 per hour and the highest average salary per sector is $41.93 per hour and we take the difference between the two which is $15.84 and apply that to an average work week which is 35 hours and an average of 49 weeks of work per year we arrive at a value of $27,166 per participant.

- Communal Taxation – Canada Revenue reports that the Federal Marginal Tax rate for 2018 for those earning less than $46,605 is 15%.[17] The Ministry of Finance in Ontario reports that the Provincial Marginal Tax rate for 2018 for those earning $43,906 or less is 5.05%.[18] To calculate the contribution in this area we multiplied the value in the previous column by 20.05%

- Civic Engagement – The National Endowment for the Arts in the United States estimates that youth involved in arts programming contribute 17% more volunteer hours on average over the course of their lives than those that are not. Moreover, their findings suggest that they contribute 4% more than the general population.[19] Imagine Canada estimates that Canadians contribute on average 156 volunteer hours per year.[20] When we consider that Conference Board of Canada recognizes $27 per hour for every volunteer hour contributed by Canadians[21] we can apply a value based on 156 hours plus 4% times the number of participants times $27. We also recognize that while there are other aspects of civic engagement that can be monetized, we have limited the value applied in this study to the increased volunteer potential.

- Health and Social Network Savings – The Arts Network for Children and Youth reports that when individuals have access to the arts and other creative activities studies show lower high school drop-out rates, there is a reduction in crime, reduced psychosocial behaviour and improved health and social skills. The Network adds that these benefits come with “considerable reduction in costs to the social, health and justice sectors.[22] Arts Health Network Canada states that arts and culture have been shown to lower costs and improve the sustainability of health care systems as well as make substantial contributions to individual and community health.[23] For example, a 2014 British Parliamentary Study suggests that individuals who are engaged in the arts in some way are 5.4% more likely to report good health (controlling for factors like income).[24] Despite the abundance of research in this area there is little quantitative research documenting the socio-economic relationship between the arts the health. In 2008, Hankivsky reported that the cost to the social network of one student dropping out of High School was $12,552.[25] The value of this in 2018 is $14,693.62. Similarly, the Toronto Arts Foundation reports 82% of students who participate in structured arts programs are finished High School compared to 68% of those who did not. Based on these studies we can estimate that 14% of the youth participating in formal arts/music programs are less likely to drop out of school and therefore have a positive socio-economic contribution to the social network of $14,693.62 annually.

- This translates to an average value of $2,661 per participant.

D. Magnet Effect

13-22. Conferences, weddings, funerals, religious festivals and rites of passage and other events often attract significant numbers of visitors to the congregational site. These visitors often spend significant amounts of money while in the neighbourhood. In total, we identified 10 areas that contribute to “Magnet Effect”. In the Philadelphia study, Cnaan et al (2013) attempted to differentiate between the numbers of people who might travel overnight for an event vs. those who were simply making daytrips into the community. In our study, we elected not to include overnight stays, believing these estimates would be too difficult to verify. Instead, we opted to make use of Ontario Ministry Tourism estimates that place the average same day visit spending to be around $82. Applying the same rationale used by Cnaan et al (2013) to apply this value to only 1 in 4 visitors, we settled on an average value of $20 per visitor. We then applied either reported estimates of those travelling greater than 10 km to each event or applied the corresponding percentage of worshippers who travel more than 10km to worship as a proxy.

23. Members Expenses While in the Neighbourhood: As illustrated in sections 12-21, visitors to the neighbourhood are estimated to spend an average of $20 per visit. If the individual, or family, simply drive in and out of the neighbourhood, their financial contribution will be minimal. But if they purchase gas, buy groceries, visit a local resident or go shopping at a nearby mall their spending will increase significantly. In the Philadelphia study, estimates of this daily value were confirmed with over 30 interviews of members who commute from outside the neighbourhood to attend services. As a result, we applied the same $20 amount per person for those travelling greater than 10 km to worship. (This does not take into account times when they may have driven in to attend mid-week meetings or programs).

E. Individual Impact

24. Suicide Prevention: Assessing the value of life is a difficult topic socially, let alone in financial terms.[26] It is commonly assumed that the two key costs of suicide and attempted suicide are lost income and cost of health care. This assumption excludes the notion of attributing a value to the grief of family and friends. The Canadian Mental Health Association reports that the cost of suicidal death ranges from $433,000 to $4,131,000 per individual depending on potential years of lost life, income level and economic impacts on survivors. The estimated cost of attempted suicide ranges from $33,000 to $308,000 per individual depending on the level of hospital costs, rehabilitation, family disruption in terms of lost income, and support required following the attempt.[27] While it is difficult to assess whether or not preventing a suicide over the course of a year prevents suicide in subsequent years, we followed the assumption offered by Cnaan et al (2013) that it can conservatively be estimated that preventing someone from committing suicide for one year saves a 20th of the cost of suicide. Using their model, we added $33,000 (the lowest estimate of the cost of attempted suicide) and 5% of $433,000 (the lowest estimated cost of a successful suicide) to arrive at a value of $54,650. It should be noted that this figure does not include an economic value for the cost of grief, emotional trauma, and other personal suffering.

25. Helping People Gain Employment: Many congregations are active in helping congregational members and/or community residents gain full-time employment. In order to assess this value, we use the corresponding provincial minimum wage for each study congregation at a conservative estimate of 35 hours/week for 50 weeks per year. In Ontario, in 2020, the current minimum wage is $14 per hour. This translates to a corresponding annual salary of $24,500.

26. Crime Prevention: Some congregations also report that they have been active in preventing congregational or community members from going to prison. Cnaan et al (2013) report that this should be seen as a distinct from the general influence congregations may have as examples of “moral influence” (i.e. promoting good behaviour, social cohesion and respect for the law). In this section of the study, however, we are focussing on direct impact, examples of crime prevention where clergy or other members of the congregation were directly responsible for preventing this kind of outcome. Statistics Canada reports that it costs an average of $357 each day to maintain an adult in federal prison and $172 to imprison someone in Provincial Correctional Facilities.[28] To arrive at an appropriate index we took the average of the two ($264.50) and multiplied the figure by 365 for a total of $96,542.50. To this figure, Cnaan et al. added a figure of $5,000 in minimum taxes that the government no longer receives from the imprisoned person, bringing the total to $101,542.50. We applied this value each time a congregation reported directly preventing someone from going to prison.

27. Helping End Alcohol and Substance Abuse: Many faith communities are also active in helping people end alcohol and substance abuse. While there may be indirect assistance offered by being connected to a faith community, as well as membership in affiliated support groups such as AA, our study involved only direct counselling from clergy or other congregational staff. We asked each clergy team to identify the number of individuals they believed they had had a direct role in ending a person’s alcohol or substance abuse. Then in order to value this contribution we reviewed the literature on economic cost of these factors on society. In 2002, it was estimated, that the economic costs to society of substance abuse have reached $39.8 billion in Canada[29]. Of these economic costs, approximately $24.3 billion was due to labour productivity losses, including short-term and long-term disability and premature mortality. Health Canada estimates that social costs for alcohol and substance abuse are comprised primarily of health and enforcement costs. In terms of alcohol related costs they estimate $165 (health) and $153 (enforcement) for a total of $318 per occurrence. With respect to substance abuse they estimate $20 (health) and $328 (enforcement) for a total of $348. This leaves us with an average value of $338 per occurrence.[30] It should be noted that these figures are considerably lower than the estimate of $15,750 put forward by Cnaan et al (2013).

28. Enhancing Health and Reducing the Cost of Illness: The Canadian Institute for Health Information reports that the average health costs per person are $6105 annually.[31] It has also been reported that early diagnosis (particularly in the area of dementia and diabetes which represent two of Canada`s greatest public health challenges) can reduce health costs by as much as 30%.[32] Taking these figures into account we applied an index value of $1831 in situations where congregations have through some means been able to assist with early diagnosis or access to health care. While this is often difficult to assess it is most clearly evident in situations where a Parish Health Nurse or some other Medical or Mental Health Professional is part of the congregational staff.

29. Exercise Programs: Katzmarzyk and Jansen (2001) estimate that inactivity accounts for 2.6% of the total annual Canadian Health Cost. In 2016, that value was estimated to be $219 Billion. 2.6% of that amount is 5,694,000,000 or approximately $5.7 billion. Canada’s population in 2016 was 36,268,378 which equates to $156.70 per person. As a result, we applied $157 to every person who the congregation involved in a regular program of physical activity.

30. Teaching Children Pro-Social Values: Cnaan et al (2013) point out that one of the reasons families with young children join faith a community is to ensure that their young children receive a moral education, are taught social values and learn something of the value of civic engagement. Regardless of religious tradition, communities of faith offer educational programs and children`s activities that encourage social responsibility, moral commitment, and respect for authority. These programs are difficult to value. For the most part, the costs for these programs are embedded within congregations` general budgets. Cnaan et al contacted some groups who did charge for youth programming and devised a formula which suggests the value of teaching a young person pro-social values is $375 per year. We were unable to identify similar programs in the Canadian context. One way of valuing this role would simply be to apply the current CDN exchange rate to the figure proposed by Cnaan et al. This would produce a value of $484.25. Another way would be to ascribe a modest value of $10 per week which would equate to an annual value of $520 (very close to the proposed exchange rate (to err on the conservative side we elected to go with $484.25 per identified child 12 years and under).

31. Promoting Youth Civic Engagement: Several studies support the economic value of teaching youth civic behaviour.[33] They contend that religious participation, as well as participation in other forms of extra-curricular activities is a significant predictor of political and civic involvement and that these youth are less likely to engage in risky behaviours that bear cost to society. Sinha et al[34] are careful to note that congregational influence represents only one of many factors including parental care, school input as well as peer influence. In terms of ascribing economic value to this dynamic, the clearest offering we were able to identify is put forward by Cohen and Piquero.[35]They suggest that the potential benefits of encouraging civic behaviour is similar to that of dissuading a young person from adverse societal behaviours such as truancy, drug use, criminal activity and abusive behaviour towards peers. They conclude that the monetary value of “saving” a high-risk youth is between 2.6 and 5.3 million dollars (US). With a midpoint of approximately 3.95 million over a 50-year lifetime, the annual savings is approximately $79,000 (USD) or $102,013 (CDN). However, not all youth are “high-risk” and so we reduced the estimate by 75% (1 in 4). Furthermore, faith communities are not alone in helping youth avoid illegal or risky behaviours. Parents, teachers and other organizations all have a role to play in supporting them. And so, we reduced the figure by another 75%, arriving at a final estimate of $6379 (CDN) annually for each identified youth between the ages of 13 and 18.

32. Helping Immigrant and Refugee Families Settle in Canada: To apply value in this area our earliest studies relied on a report by the Ontario Council of Agencies Serving Immigrants reports that it costs an average family of three approximately $55,000 - $65,000 a year for living expenses. Many faith communities are involved in sponsoring refugee families from abroad.[36] This includes not only covering these costs for a period of up to one year but assisting with: helping to find suitable long-term housing, helping to learn English or French, assisting with job search, helping them to learn about Canadian culture and values, and helping them to access services and programs within the community. Assuming that there are costs beyond the minimum average “hard” cost of $55,000, early in our assessments we took the difference between the two estimated values to apply a valuation of $60,000 per family (in this case regardless of family size). Suspecting, however, that this value was low, we asked five of the study congregations who had been involved in refugee sponsorship to provide detailed estimates of time spent, in-kind donations and factored these values alongside study estimates of the socio-economic benefit for society of these activities. As a result, we estimate the value of sponsoring a thee-member family to be $124,942[37]

33. Preventing Divorce: Clergy sometimes are able to support married partners in ways that help to prevent divorce. In order to measure this impact, we asked clergy to indicate the number of married partners that they could reasonably state would likely have separated or divorced without their direct influence. In Canada, an uncontested divorce will cost approximately $1,000. However, a recent poll of 570 Canadian lawyers indicates that cost for a contested divorce ranges from $6,582 to as much as $86,644, with the average running about $15,570.[38] It is recognized, however, that the prevention of divorce by a ministry professional such as Pastor, Rabbi or Imam or any designated members of a congregation may not be permanent. Couples may simply be postponing divorce until a later date. For this reason we followed the example of Cnaan et al, counting the figure of $15,570 as being applicable if the couple stayed together for another 20 years. Dividing by 20, we estimate the value of preventing a divorce for one year is worth approximately $780.

34. Helping End Abusive Relationships: In 2013, Justice Canada released a report indicating that domestic violence and spousal abuse costs the country at least $7.4 billion a year.[39] Drawing on almost 50,000 instances of spousal abuse reported to police, and a 2009 Statistics Canada phone survey which estimated that 336,000 Canadians were victims to some form of violence from their spouse. Dividing the estimated cost by the number of victims yields an annual per victim cost of $22,023. As with divorce, it is possible that prevention may not be permanent. Applying the same 20-year logic model, dividing by 20, we estimate the value of helping end an abusive relationship for one year to be worth approximately $1100.

F. Community Development

35. Job Training: Congregations, particularly in urban settings, are often involved with individuals in need of job training. In 2006, Cnaan et al conducted a census of congregations in the City of Philadelphia, in which they asked about the cost of congregational-based job training programs. The reported average cost was approximately $10,000 per program. Our study chose to address this question differently; on the basis of per individual cost. To approximate an appropriate value we explored other publicly offered programs. The YMCA in Toronto offers courses that provide one-with-one counselling, assessment tools such as Myers Briggs and Emotional Quotient Inventory, detailed interpretation of the assessment results and follow-up sessions for ongoing support and guidance. Depending on the amount of time these programs range and length of ongoing support these programs range from $470 to $610 to $870.[40] Assuming that most individuals would choose the middle category we settled on a figure of $610 per individual for job-training programs.

36. Housing Initiatives: Housing programs are amongst the most demanding types of projects that congregations can undertake. They require substantial amounts of funding, long-term commitment, and the support of a wide variety of partners and stakeholders. In cases where congregations have undertaken these commitments we propose calculating direct costs for construction pro-rated over an assumed 50 year life-span. In addition to this, Toronto Community Housing Identifies a market value rate of $1060 per family-sized unit.[41] In order to attribute an approximate value to society for Housing Initiative Involvement we adopted the following equation: (cost / 50 years) + (number of units created x $1060/month or $12720) minus rent paid and government subsidies applied.

37. Lending Programs: Faith based organizations, including local congregations, have a rich tradition of involvement in developing the social economy of Canada.[42] One such example is where faith-based organizations have been involved in lending programs to assist families in extreme need or to facilitate small business and micro-industry. In cases where congregations have undertaken this kind of support, we propose basing value on the actual amount of funds loaned.

38. Small Business and Non-Profit Incubation: Some faith communities are involved in helping incubate or initiate small business or micro-enterprises. Cnaan et al[43] found that the average investment of congregations who were involved in incubating small businesses was $30,000. In our study, we chose to use employment generated. Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada identifies a micro-business as 1 to 4 employees.[44] We assumed that any start-up business would likely fall within this category. We estimated an average number of 2 employees unless specifically stated. Again using the minimum wage calculation for two individuals we arrived at a total annual value of $39375 for the creation of a small business. This estimate is conservative and does not take into account the investment of the owners or taxes generated.

G. Social Capital and Care

Most faith communities, regardless of tradition provide space for social programming that benefits people in the wider community. For the most part, their operating budget covers at least part of the cost of these programs. For example, the cost of clergy and staff time, utilities and building maintenance are generally included in operating budgets. Some additional costs; however, are not covered. They include the following three items: space value, volunteer time, and in-kind support.

39. Value of Social Program Space: We asked congregations to complete program templates for each program they provide or support that is open to and provides some touch-point with the wider community. Following Cnaan et al, we followed the replacement method which assumes that if a public or private organization was to provide this program, they would have to rent an equivalent space. Following this method, if a faith community provides its social program space for free, then the value of the space represents an economic contribution to the local community.[45] If the congregation rents out the space at below-market value, then we applied the difference between market value and what was received in fees. To determine market value costs for use of space we relied on information published by the local school board in each locale. For example, for the 2019/2020 school year the Toronto District School Board charges the following rates:[46]

NOTE: The figures represented above do not account for any security, technical, or client support services that are often provided and/or required by the Toronto District School Board in addition to the rates indicated above.

In situations where groups have continuous and/or exclusive use of space we have approximated based on publicly advertised lease rates for equivalent space in that locale.

Where the participating group is charged market value for the space, we applied a value of $0.

40. Value of Volunteer Time: Volunteers serve as a major resource for all congregations.[47] According to the 2011 United Nations State of the World’s Volunteerism Report, “…volunteerism benefits both society at large and the individual volunteer by strengthened trust, solidarity and reciprocity among citizens, and by purposefully creating opportunities for participation.”[48] In 2010, Statistics Canada conducted the most detailed study of volunteerism in Canada to date. Notably, for this research, StatsCan observed that 21% of people who attended religious services once a week were considered top volunteers, compared with 10% of people who attended less frequently (including adults who did not attend at all). Moreover, the StatsCan study revealed that almost two-thirds of Canadians aged 15 and over who attended religious services at least once a week (65%) did volunteer work, compared with less than one-half (44%) of people who were not frequent attendees (this includes people who did not attend at all). The study also revealed that, volunteers who are weekly religious attendees dedicated about 40% more hours than other volunteers: on average, they gave 202 hours in 2010, compared with 141 hours for other volunteers.[49] We considered volunteer work in two areas: a) operating the congregation, b) providing social programs. Our earliest studies cited a value of $24 for every volunteer hour contributed.[50] More recently however, Statistics Canada has upgraded this value to $27 per hour.[51]

41. Social Program In-Kind Support: Many congregational programs directed towards the community are supported through various types of in-kind support. A typical example would be a food or clothing drive. Sometimes these involve one-time events or supporting ongoing programs. Other types of in-kind support include transportation, school supplies and household items. For each social program the congregation reported on we asked them to estimate the amount of in-kind support they provided. We added these estimated costs across the various programs to estimate an annual contribution.

It should also be noted that in some cases, a benefit for some may be a detriment to others. Cnaan et al[52] cite the example of where a member of the clergy may help to prevent a divorce which may benefit that family but might undermine the business of local divorce lawyers. Our study does not attempt to measure.

References Cited

[1] Curran, Deborah (2011), “Economic Benefits of Natural Green Space Protection (The POLIS Project on Ecological Governance and Smart Growth BC)”. Available from: http://www.smartgrowth.bc.ca/Portals/0/Downloads/Economic%20Benefits%20of%20Natural%20Green%20Space%20Protection.pdf